The rescue operation

A poor immigrant to the U.S.

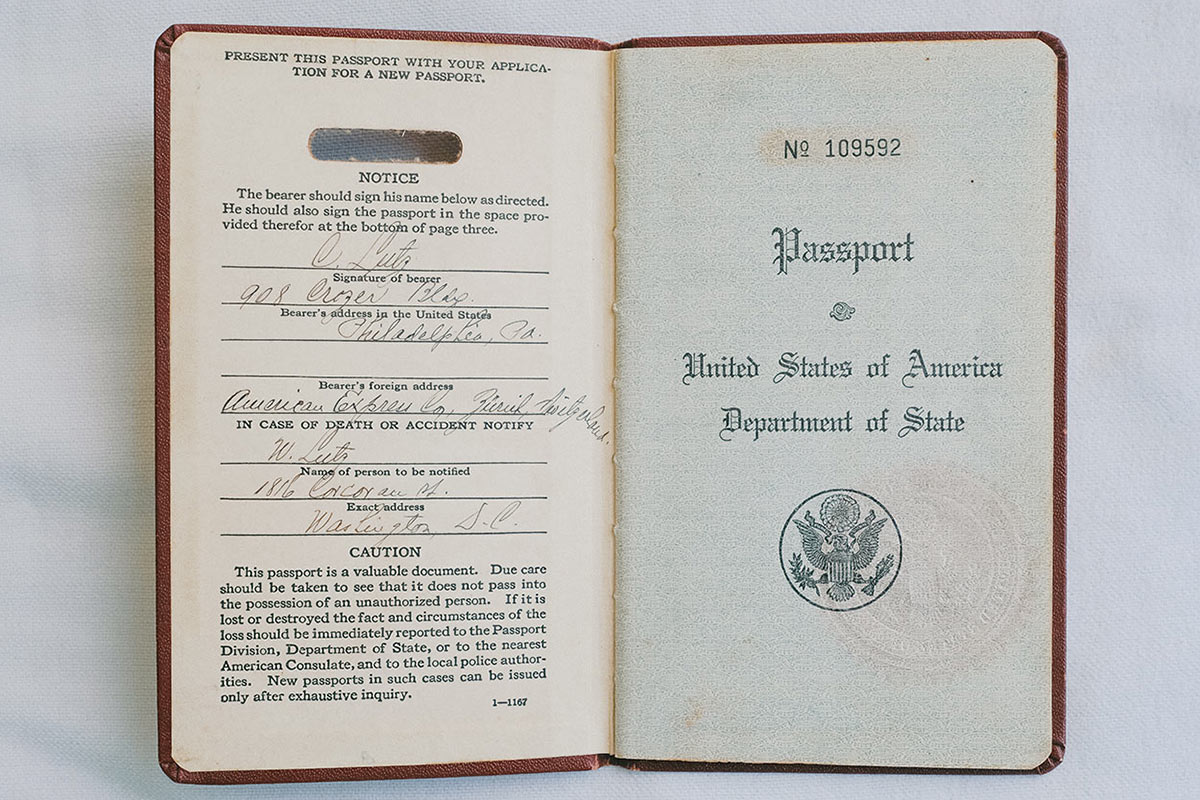

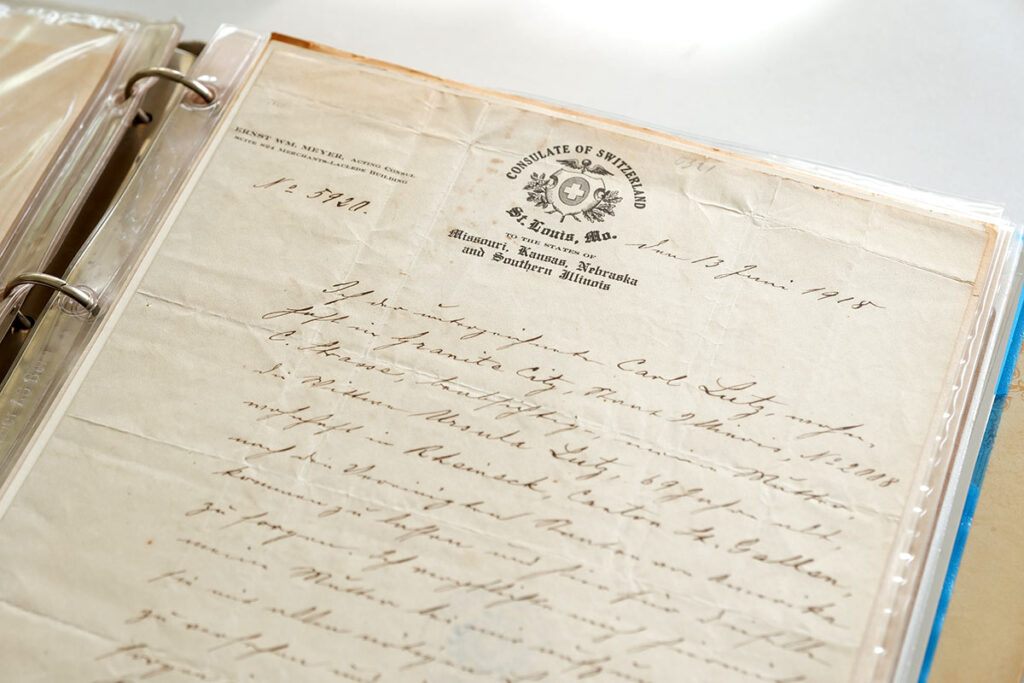

Born in Appenzell on March 30, 1895 into a large family, Karl Robert Lutz decided at an early age to emigrate to the USA (1913), to escape poverty. Joining a family friend in St. Louis (MO), he anglicized his name to “Carl”.

After a few odd jobs in Granite City, Illinois, he attended Central Wesleyan College in Warrenton, neighboring Missouri. The college was threatened by financial difficulties and closed. In search of steady employment, Lutz emigrated again, to Washington, D.C.

In 1920, the Swiss Legation (as embassies were then known) recruited him. Rigorous, he was noticed by the head of the post, who advised him to get an education. Young Lutz studied law and history at George Washington University, graduating in 1924. During his stay in the American capital, Carl Lutz lived at Dupont Circle, in the city center, now occupied by the staff of the U.S. State Department. A plaque bearing his name is affixed to the building.

Finally admitted to a consular career, the young Lutz worked in various Swiss representations in Philadelphia (Secretary of the Chancellery, 1926-1933) and St. Louis (Chancellor, 1933-1934) for ten years. On July 25, 1929, he became an American citizen, while retaining his Swiss nationality, which was still permitted in the consular service.

On a personal level, Carl Lutz married his compatriot Gertrud Fankhauser in 1935.

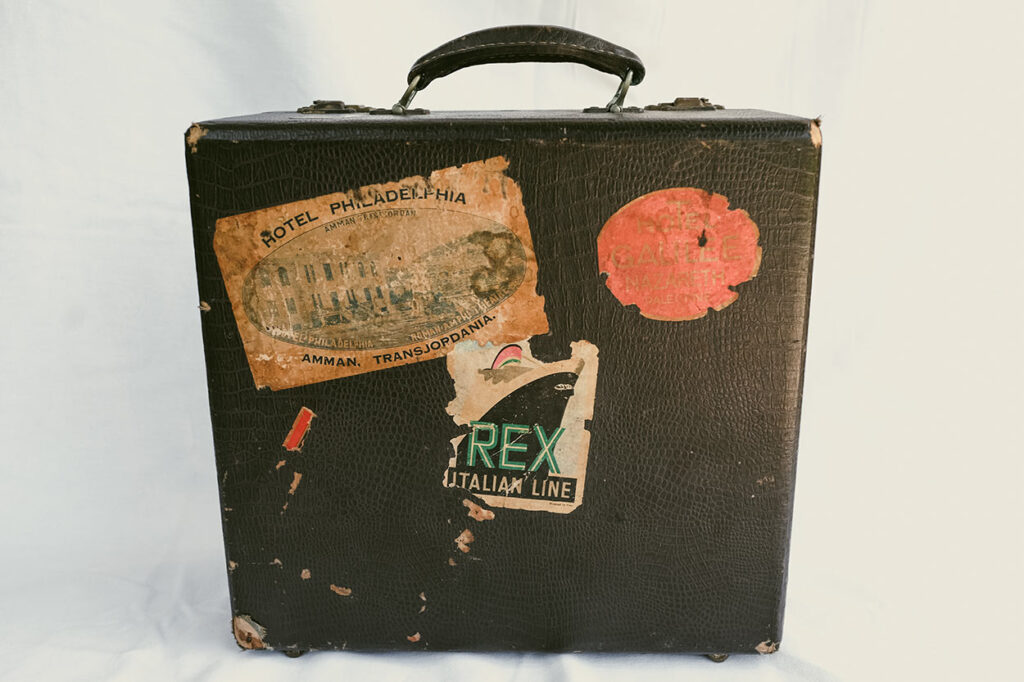

A turbulent journey to the Orient

The period 1935-1940 marked a decisive turning point in Lutz’s life and shaped his rescue work in Budapest. In 1935, he was appointed Chancellor of the Swiss Consulate in Jaffa, Palestine, under British Mandate.

In addition to 2,500 German residents, Chancellor Lutz had to deal with the arrival of some 80,000 Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. A man who used to watch current events from a distance became interested in the cause of the persecuted Jews, and heard their testimonies.

A privileged witness at a pivotal time, the civil servant witnessed the beginnings of the century’s conflict in the Middle East:

“Basically, [Lutz] only left this dangerous and effervescent Palestine in reverse. The British, through the power of their mandate[,] knew well how to pit the Arab and Jewish populations against each other, depending on the momentary situation. They either supported the Arabs against the Jews, or the Jews against the Arabs. Public safety was bad.”

Alexander Grossman

When war broke out in 1939, Germany asked Switzerland to represent its interests in Mandate Palestine (goods and people). Carl Lutz was entrusted with this task. His first act was to promptly remove the German Consulate’s swastika, which was causing disgust among Jerusalemites. It was replaced by the neutral colors of Switzerland.

Lutz did his task brilliantly. The German State praised his actions, in particular for protecting German citizens held in prison camps.

In 1941, Lutz was briefly sent to Berlin for six weeks to manage Yugoslav interests. The invasion of Yugoslavia brought this mandate to an end.

Budapest : in charge of foreign interests

At the beginning of 1942, Carl Lutz was promoted to vice-consul. He was appointed to the Swiss Legation in Budapest to represent the interests of 14 foreign countries that had broken off diplomatic relations with Hungary, including the USA and Great Britain.

In this capacity, the vice-consul enjoyed a dream life on the spot: he lived in the British Empire Residence on the royal hill of Buda, rode in the Packard limousine of the American head of post, and worked in his offices on Liberty Square, which is still the U.S. Embassy in Hungary today.

But luxury came at a price. The professional task was grueling, with nearly 3,000 in 1942 (to 10,000 in 1944) foreign nationals to protect. In addition to the two Anglo-Saxon giants, the vice-consul had to watch over the goods and people of Canada, Belgium (occupied), Chile, Egypt, Haiti, Yugoslavia (occupied), Honduras, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela, El Salvador (from July 4, 1944) and Romania (from August 25, 1944).

Above all, he had to manage a task that fell outside his strict mandate, and which was “tolerated” by Berne on “humanitarian” grounds : organizing Jewish emigration, strictly restricted, to Mandate Palestine. In fact, diplomatic cables show that Switzerland was reluctant but conceded to please British diplomacy.

In 1939, Great Britain had published a Third White Paper. This text restricted immigration to Mandate Palestine to 75,000 Jewish individuals between 1939 and 1944, as refugees – with an starting quota of 25,000, granted by London “to help resolve the Jewish question”, and a maximum of 10,000 migrants per year, from all over Europe. Carl Lutz was responsible for implementing this treaty in Hungary.

From April 1942 to December 1943, the Swiss civil servant allowed the emigration of 8,343 Hungarian Jewish children via Romania and the Black Sea port of Constanța.

In fact London’s request had been initially refused by the Swiss administration. Berne saw it as an abuse of the defense of foreign interests – Hungarian Jews were not British citizens – and an humanitarian task that should be given to professionals of the Red Cross (ICRC). The Swiss administration wrote to Lutz :“It is well understood that such steps can only be taken on a humanitarian basis and do not fall within the scope of representing foreign interests. For this reason, the head of the Department wishes you to act with the utmost caution.”

Switzerland conceded to Great Britain’s insistence, for the migration of 200 children. London specified that this was an “one-off request”. This would not be the case. Asked to organize a new departure of 180 Jewish orphans, Lutz did not tell his superiors and placed the children directly under his protection, formalizing the migration with the Palestinian Representative Office. The Swiss civil servant only informed his hierarchy once the departures were finalized, presenting it as a fait accompli.

This is the first indication that Lutz, who was more sensitive to the Jewish plea than he should have been as a consular officer, was not toeing the official line.

The occupation of Hungary

On March 19, 1944, Germany invaded Hungary, fearing that Hungary would switch sides and fan the front line. Hitler imposed a President of the Council of Ministers favorable to him, while keeping the historic Regent Horthy at the head of the country.

Overnight, conditions for the Jews, already poor, became desperate. The German state, led by SS Lieutenant-Colonel Adolf Eichmann, instituted terror: Jews had to wear a yellow star, were forbidden to travel, had their property confiscated and were arbitrarily arrested. Hungary was divided into six zones, isolated from each other. The territories of annexed Transylvania were sealed off.

From April 16 to July 7, 437,402 Jewish civilians from the Hungarian provinces were placed in ghettos and, from May 15, deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in occupied Poland. The SS photographic service took the only known photos of the selection and the arrival of the civilians, after days of transport without food or sleep.

Within 56 days, a vibrant, well-integrated minority had disappeared from its own country. All that remained were the 180,000 Jews and 62,000 converts in Budapest. At the end of June, they too were confined to “Yellow Star Houses” awaiting deportation.

On June 19, 1944, while the slaughter of provincial Jews was being carried out with unparalleled speed, Carl Lutz leaked to a visiting Romanian visitor what came to be known as the “Auschwitz Protocols” – the “first document detailing the gas chambers and crematoria to have been taken seriously abroad”, writes Prof. Linn of Haifa University.

The reality of the Auschwitz protocols was the subject of a symposium at New York University in 2011. The Carl Lutz Society carried out further research on the subject, presented at the Auschwitz State Museum in 2019.

This whistle-blowing initiative, a serious breach for a civil servant like Carl Lutz, was not discovered. The report was secretly brought back to Switzerland, to Geneva. A “diplomat” from El Salvador, with whom Lutz exchanged correspondence, distributed the documents to the Swiss and international press on June 24.

The Auschwitz Protocols – and more precisely their Hungarian amendment, sent from Budapest – would be covered by major media of the neutral and Allied nations, including in England, Canada and the United States, starting on June 26, 1944 and up to the end of July, during the U.S. Presidential campaign.

383 articles were featured in Switzerland alone, in 120 media and within a month. “Until now, we knew that the Jews had been deported. We also knew that they were not treated tenderly, wrote a Swiss journalist. But even Germany’s greatest enemy would not have dared to say that in mid-May 1944, sixty-two wagons carrying Jewish children had been gassed and their bodies burned in Oświęcim, Poland. No one would have believed such a thing”.

Hungary was embarrassed, as was German diplomacy. Throughout the summer of 1944, the entire Hungarian-German network was mobilized to deny the existence of the killing, including press conferences at the German and Hungarian Foreign Ministries, the creation of propaganda films and radio broadcasts.

The SS officer in charge of the deportations, Adolf Eichmann, on the other hand, reacted differently: “Eichmann was particularly vain of the fact that his name was also mentioned in the foreign press in connection with his work on the Jewish question. He kept a special file with these press clippings, testified Theodor Grell, of the German Legation in Budapest. He was grateful if I could give him a hint here or there. Apart from a few articles in the foreign press which he was unable to read for lack of language skills, I remember in particular an article in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung on Auschwitz, in which his name was also mentioned”.

Regent Horthy’s government, under political and media pressure, destabilized by the Soviet advance on the front and threatened internally by the militia, announced the suspension of deportations on July 7, 1944.

“Deportations in the country were already continuing. We already had accounts of the disarray at Auschwitz from a few Polish and Slovak Pioneers who had managed to escape. That’s why we felt it was so important to awaken public opinion abroad, as a matter of urgency.

He [Moshe Krausz] collected data on the deportations to Hungary, attached details of all the misery they brought, and added them to the Auschwitz testimonies. This request [the Auschwitz protocols] was forwarded abroad – thanks to Consul Lutz – by a Swiss courier, and the results followed surprisingly quickly […] as we learned from the Swiss newspapers sent to us a few weeks later.

(Some newspapers published our documents verbatim, such as the Neue Züricher [sic] Zeitung on the deportation of Nyíregyháza).”

Statement by a Carl Lutz employee to Hungarian investigators, February 12, 1946

As a defender of British interests, Carl Lutz kept a list of 7,000 Jewish adults and 800 children authorized to emigrate to Mandate Palestine, administered by London.

This migration was a source of tension between the Allies, Hungarians and Germans. It opened up a real administrative battle between the belligerents. And this is reflected in diplomatic documentation.

As for the form, the figure changed in the correspondence, either through typographical error or deliberate sabotage attempts: Lutz spoke of “around 6,000 adults and 1,000 children” (as at June 1), the German plenipotentiary mistakenly reported “8,700” (July 25), the British reduced this number to “5,000” to blame Lutz for his zeal (August 3) and then the Germans, seeking to block the process, issued only 2,000 exit visas (August 3). They kept the Legation waiting throughout the autumn, while the Americans (December 11) reported that Switzerland was authorized to organize departure for only “7,000 people”. “The transfer of 1,000 children has not yet been formalized”.

On the substance, however, the formal quota remained unchanged. It was 7,800 “individuals”; this was the figure Carl Lutz gave to his Federal Councillor (Minister) on December 8, 1944. And it’s the figure on which historians today agree.

As part of his good offices, Lutz was authorized to issue letters of protection (“Schutzbrief”) for these 7,800 people. Pending their departure, the Jews were thus under Swiss consular protection. In effect, they were exempt from compulsory labor and possible deportation.

On July 15, 1944, Lutz met a young Swede, Raoul Wallenberg, who had arrived in Budapest on the 9th. The latter, who had initially come to exfiltrate 649 Jews, learned from his Swiss colleague of a completely different plan: to extend protection to entire families, “tens of thousands” of people, by diverting the consular tools at his disposal.

Wallenberg was “shocked” by the scale of the project, which had no institutional basis.

Documentation shows that Lutz was already clandestinely distributing false documents of all kinds to Jews at the time. But he wanted to increase the size of this effort. It was this reputation that led the young Swede to meet him.

“Shortly after Wallenberg’s arrival in Budapest in the summer of 1944, he visited me at the American Legation on Freedom Square. He told me that he intended to lead an operation to rescue persecuted Jews.

He then asked me to give him the text of the Swiss letters of protection, and I also told him about my other actions on behalf of the Jewish population. I informed him as much as I could.”

Carl Lutz, 1966

From now on, Lutz and Wallenberg would work together, in coordination with the diplomatic corps on the spot.

Wallenberg changed tactics: he asked for 4,500 Jewish civilians to be protected, for whom he had Swedish passports (“Schutzpass”) issued. The young man eventually placed between 7 and 9,000 Jews under his permanent protection, and ran a vast network of protected buildings and soup kitchens.

Extraordinarily courageous, he would be remembered as the Righteous foreigner who took the most personal risks in Budapest. He was eventually captured by the Soviets at the end of the war and executed in Moscow around 1947, in obscure circumstances.

The differences between Carl Lutz and Raoul Wallenberg were central: the Swede’s effort was fully endorsed by his hierarchy at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Stockholm. Wallenberg was authorized to issue identity papers, declaring Jews of Hungarian origin to be Swedish. His capital had made the political choice to integrate these migrants after the war, on humanitarian grounds, should they make their way to Sweden. Swiss staff had no such guarantees.

Furthermore Wallenberg was originally commissioned by the United States (War Refugee Board) and Sweden, in a joint rescue effort. The young man also had access to a humanitarian budget to carry out his mission, a detail that left its mark on Swiss personnel, who were forced to rescue Jews without authorization, and without a penny.

Logically, Wallenberg’s rescue operation, politically approved and rewarding for both Sweden and the United States, would remain a central part of the memory of both countries.

Confronting Eichmann

In his protection plan, Carl Lutz intended to exploit an administrative loophole: Germany and Hungary were considering the departure of a strict contingent of migrants to Palestine, i.e. 7,800 Jewish individuals.

As head of the Foreign Interests Division in Hungary, the Swiss Vice-Consul pleaded their cause with Adolf Eichmann, the SD officer in charge of the “Jewish question”.

Eichmann rejected the migration of Jews to Palestine. According to German diplomatic correspondence, he was looking for ways to eventually divert the Swiss convoys. But while he was planning the genocide, the fact that Carl Lutz was dependent on a defined quota of civilians was an advantage. The SS officer saw this as a form of hostage-taking. If it wanted to save his quota of 7,800 Jews, wouldn’t the Swiss personnel in Budapest have to keep quiet in the face of other abuses?

The contingent of refugees was finally approved by Hungary on June 27, then by Germany, Hitler himself, on July 10, 1944.

On July 19, Carl Lutz reported to the Allies that Hungary was ready to authorize the departure of any Jew “bearing safe-conduct” to Mandate Palestine. Faced with this timid overture, Lutz got his foot in the door.

The refugees were so numerous that the administration divided them up. To make things easier at the borders, Lutz traditionally divided the Jews into different “units”. Every five people, on average, received a single document valid for all their relatives. They should travel together. Once at their destination, the British customs authorities only had to check 1,500 safe-conducts to duly register the entry of 7,800 people. The aim was to simplify migration procedures.

Carl Lutz turned this administrative subtlety upside down. On July 21, he announced to Hungarians that his Division was no longer handling 7,800 “individuals”… but 7,800 “families”. This stratagem artificially increased his quota to… “40,000 people”.

Instead of dividing his quota, he had… multiplied it.

Lutz would later describe it as a “rather extravagant idea”. The vice-consul had no consular authority, either in Berne or in London, to extend his protection to five times more individuals than his legal quota. The fraud was not small: 40,000 people instead of 7,800. This personal initiative, if learned in Berne, would earn him immediate dismissal, as historian Tschuy pointed out.

Eichmann: “You speak like Moses imploring Pharaoh. Here I am my master’s faithful servant. The Jews must be sheltered from the advancing front, to prevent sabotage in our rear. As we speak, I am thinking above all of my comrades who are freezing their feet off in Russia.”

Lutz: “Herr Obersturmbannführer, in my eyes, there are no Jews, Germans or Swiss. There are only human beings trying to save their lives. If you were a Jew, you’d come to me for help yourself.”

Eichmann: “Damn, you’ve got a lot of nerve telling me that!”

Carl Lutz to Adolf Eichmann, April 25, 1944

Lutz assumed that Hungary, embroiled in a storm of criticism over its “Jewish policy”, would have no political leverage to debate the figures – however wrong they might be. This is all the more true since several community players had been trying to obtain concessions since the deportations were suspended at the beginning of July. The tactic seemed to be working. Hungary agreed to the 40,000 figure.

Reporting back to Switzerland, an “optimistic” Lutz, as historian Braham prosaically wrote, presented the proposal not as his own, although he had no right to do so, but as a spontaneous concession by the Hungarians.

But in the end, Lutz was disillusioned. As soon as it learned of the coup, Berlin reacted.

“The Swiss Legation informed the [Hungarian] Ministry of Foreign Affairs that it had immigration certificates for Palestine for 8’700 [sic] families, or around 40,000 people in all […].

The attention of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been drawn to the fact that these figures differ very considerably from the number of “about 7,000 persons” mentioned in the register […].”

German Plenipotentiary in Hungary Veesenmayer to Berlin, July 25, 1944

Carl Lutz was rather naive in his understanding of the stakes, as he worked in a hurry. Ultimately, his aim was to gain time, knowing that migration was unlikely in view of the advancing front.

Above all, the civil servant underestimated Great Britain’s position: the Allies feared that mass immigration would be hostage-taking designed to divide them, between the Americans, who were in favor of protecting the Jews (this had little political implications for them) and the British, who controlled the potential destination, Palestine. London would have to make a strong political gesture on this issue, when its only priority interests were the stability of its Empire.

In January 1944, there were still 31,008 immigration places available, according to the Palestine Representation Office in Budapest. In December 1944, when the Third White Paper limiting immigration expired (1939-1944), 52,800 certificates had been given, out of 75,000, including Lutz’s 7,800. In the end, Great Britain did not authorize any departures outside the ordinary validation process. London extended the Third White Paper in 1945, until the 75,000 quota was exhausted, at a rate of 1,500 per month, and then banned migration.

The 40,000 were eventually rejected by all concerned. Under German pressure, the Hungarian President of the Council of Ministers claimed an “error in the notes” and backed down. Suspecting that its local representative had acted without authorization, Great Britain clarified to Carl Lutz, in August 1944, that its quota of Jews was fixed. It included “individuals, not heads of families”, wrote a British official, underlining the terms.

Germany was against, Great Britain was reluctant, as was Switzerland in its role as intermediary. It feared the knock-on effect: “We would be going far beyond the limits we have set ourselves up to now in intervening on behalf of Jews who are not, in principle, entitled to our protection. [This would] set a precedent that could lead to similar requests from other states that are also interested in the fate of the Jews.”

Switzerland’s attitude remained ambiguous. Federal Councillor (Minister) Pilet-Golaz criticized the Swiss Legation in Budapest for signing a collective petition against the deportations, then changed his mind – in the face of the insistence of his local staff. He opened the Swiss borders to the Kasztner Train (1,684 people), accepted calls to take in a certain number of refugees and conceded that the – famous – 7,800 Hungarian Jews could, on their way to Palestine, transit through Switzerland, while dismissing foreign calls to mobilize on the ground. His response to the tragedy fell far short of the substantial rescue effort led by Sweden, another neutral country. Carl Lutz spoke of “guilty indifference”.

While conducting modest humanitarian negotiations at bilateral level, Switzerland refused to allow Lutz’ Foreign Interests Division in Budapest to become involved in rescue operations. This was not its role. It could be likened to “espionage”. Lutz’s superior in Berne, Arthur de Pury, drew the line in a note addressed to Federal Councillor Pilet-Golaz (June 14): “the measures decided by the Hungarian government against the Israelites constitute a matter of domestic policy in which we do not consider ourselves bound to intervene”.

To the American insistence that Switzerland should send specialist personnel to Carl Lutz in Hungary – to prevent, namely, “the extermination of the Jews” – the Federal Councillor replied twice in the negative (June 21): “we must fight the tendency to divert the activity of defending foreign interests from what it should be.”

In the face of tragedy, Swiss personnel in Hungary felt alone. “We were abandoned by the outside world”, wrote the vice-consul in 1962.

The official quota of 7,800 “individuals” was once again the only figure accepted for negotiations.

“A Federal Councillor [Minister] said to me: – After all, you had no authority to carry out this rescue operation.

I replied: – Mr. Federal Councillor, if you see a person drowning, and his two hands come out of the water, do you have to ask for authorization to rescue him?”

Carl Lutz, interview for Swiss television, 1975

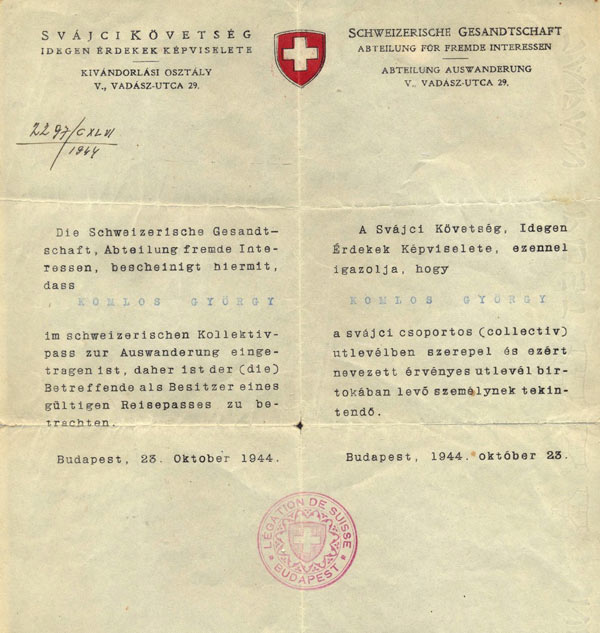

Documents that saved lives

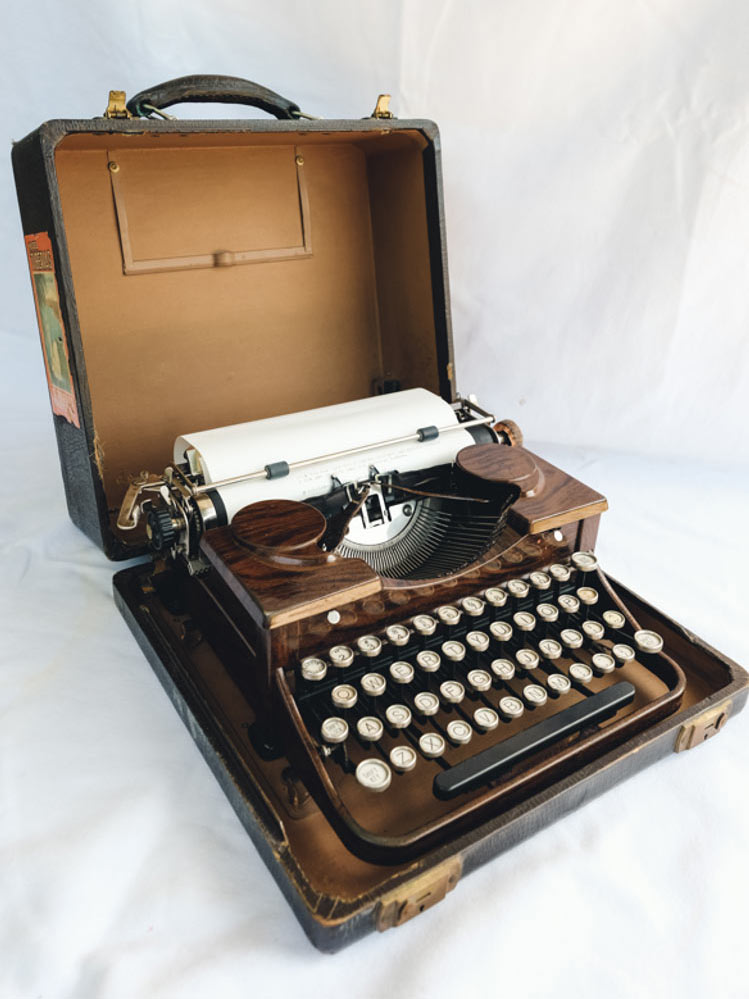

Swiss staff on the ground refused to give in. Without authorization from its superiors in Berne or its mandatory State, in London as well as Berlin and Budapest, the Foreign Interests Division in Hungary continued to distribute surplus safe-conducts. To conceal the excess, all Swiss letters of protection were numbered from 1 to 7,800, then again from 1 to 7,800, giving the illusion that the limit was respected.

By the Fall, the number of letters of protection in circulation far exceeded the strict quota. “Consul Lutz was benevolent, and on several occasions stressed that he had generously distributed the protection documents despite the strict instructions from the Anglo-Saxons”, a rabbi testified in 1945.

Lutz had almost three times as many certificates issued as he was entitled to. He had them distributed in the ghetto areas of Budapest by the Jewish resistance. Faced with imminent announcements of renewed massacres, the civil servant no longer readed the documents he signed. This tactic was all the more serious as every “migrant”, once under protection, was considered a citizen of the British Empire.

To reinforce protection, Carl Lutz spontaneously created “collective passports” on July 29 – a document he claimed to his superiors was limited to the 7,800 Jews officially in his charge. “We are astonished that you yourself have established a collective passport” was the reply from Berne, which had little taste for his agent’s largesse. The initiative earned him internal criticism years after the war.

Using the full range of consular tools at his disposal, Carl Lutz took his service beyond the call of duty to stem the tide of deportations. He diverted resources not only from Switzerland, Great Britain and the USA, but also from other countries to rescue Jews.

His choice had already been made: as soon as the Germans invaded, he had smuggled identity papers to young Jews, including Slovakian Rafi Frieldl, who had artificially become a U.S. citizen (March 19). He had also declared, without validation from London, that the Palestine Representation Office (Jewish Agency) was now the emigration service of the Swiss Legation. He had housed it within his own walls, to the anger of the Germans who wanted to deport its director.

Some refugees had received papers from Lutz declaring them “Swiss citizens”. Such was the case of the 150 Hungarian Jews who worked under his direct orders – including Simsha Humwald or Alexander Grossman, his right-hand man, who spoke German. The latter ran an office under a false name with a Swiss accent: “Dr. Alexander Kühne”.

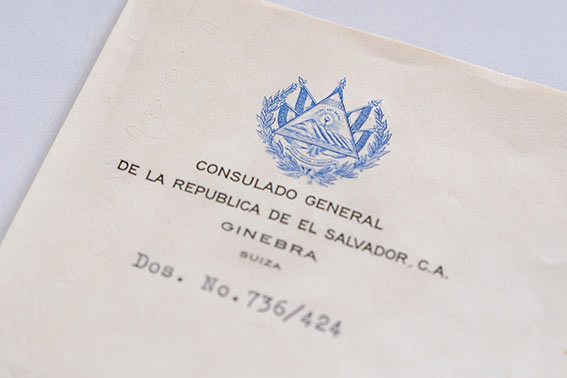

On April 26, 1944, the vice-consul had welcomed the Grausz family, a Hungarian Jewish family in distress. They had asked for help: their daughter being born in Hendon, England – she was entitled to protection. Lutz had gone beyond the call of duty: he had declared the whole family… citizens of El Salvador. Although none of them spoke Spanish or had ever visited the country, Central American citizenship proved an effective bulwark against the police. To this administrative protection, the vice-consul had added a physical barrier against the raids (April 27): he had placed the bedroom of six-year-old Elizabeth Agnes in Pest under Swiss protection. She would become his adoptive daughter.

In addition to his initial plan, Lutz distributed to persecuted Jews, by his own admission, “thousands” of falsified certificates – assuring them that they were citizens of El Salvador. Plenipotentiary Veesenmayer reported to Berlin that “20,000” Salvadoran papers were in circulation in Hungary, a figure that was no doubt extrapolated and intended to provoke a reaction in the German Foreign Ministry.

Lutz obtains these false certificates from the Salvadoran Consulate General in Geneva. First clandestinely, via visitors (including Florian Manoliu, declared Just in 2001), then mixed in with the diplomatic pouch mail, once Switzerland had taken charge of the small country’s interests. This request for representation came by the back door, Berne having refused, on June 14, to represent El Salvador in Hungary, seeing it as an abuse of the defense of interests to protect Jews, and not legitimate Salvadoran nationals. In the end, it was the Central American capital that obtained Swiss representation on the spot, via an unconventional procedure.

In Geneva, the rescue network was headed by a “Salvadoran 1st Secretary”, Georges Mandl-Mantello, in reality a Jewish immigrant and local employee. He worked in secret to protect Jews from deportation. Mantello was supported by local students paid on a piece-rate basis. Added to this network are lawyers and a benevolent translator, employed by the cantonal Chancellery, who will be investigated.

Mantello had a poor command of the French language. He wrote all the certificates in the female form – which didn’t exactly make things any easier for Lutz in Budapest, who had to add the names to the blank certificates. Little Agnes’ father, Alexander Grausz, lived with a woman ID, “reconnue comme citoyenne” (July 23). Fortunately, the SS and the militia did not speak French either.

Carl Lutz’s own future wife, Magda, a Hungarian Jew, lived with him under a false Salvadoran nationality.

The Glass House

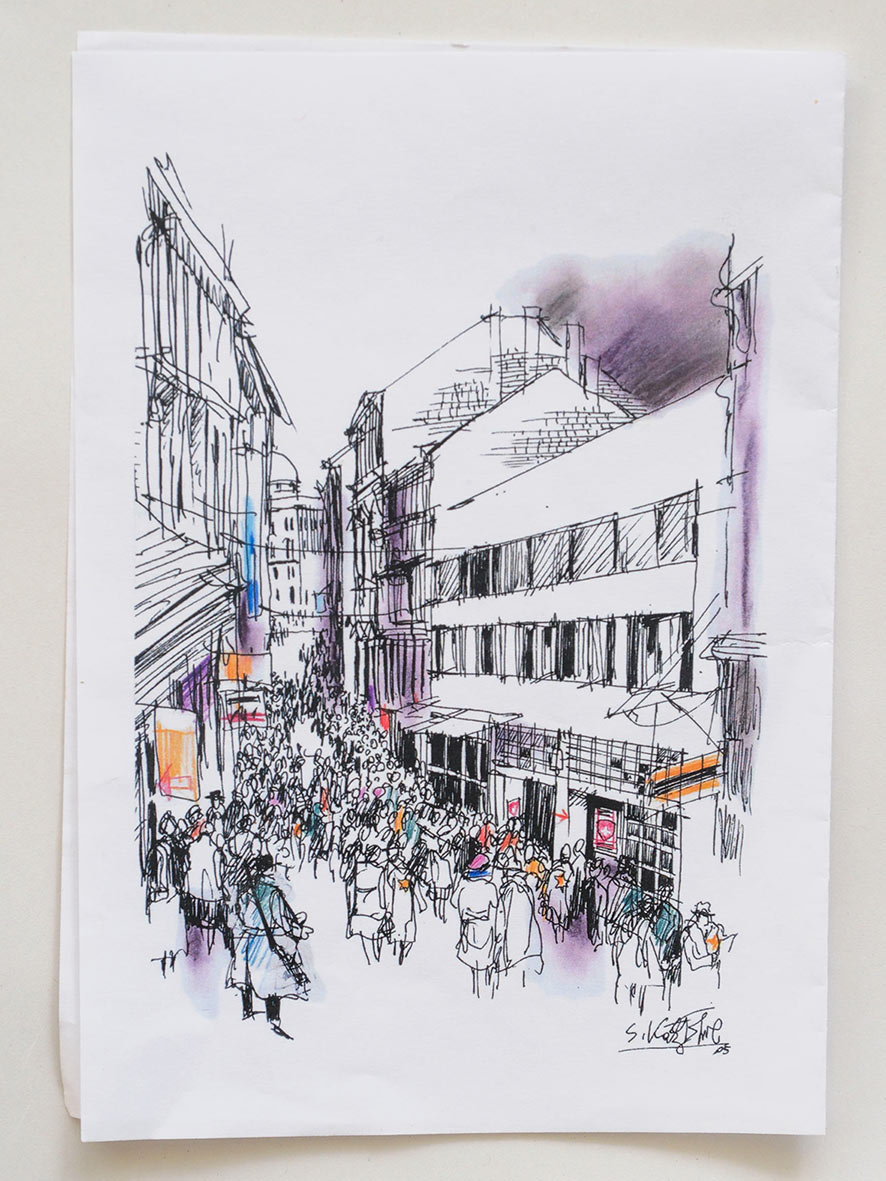

Wishing to protect his staff from explicit threats by the SS, Lutz took a new initiative: he rented the premises of a glassworks in the center of Budapest. He set up his emigration service there on July 24, 1944.

The industrial warehouse became a refugee camp for 2,750 people. Its glass walls shone “like hundreds of mirrors”, which impressed the Jewish refugees. All the more so as it was located on Vadasz Street, “the hunters’ street” in Hungarian, a sinister omen as denunciators and militiamen lurked outside.

A veritable “little autonomous society” was created, with a choir, a kitchen, classrooms, an infirmary and improvised showers. Some of the couples formed, and even married after the war. The Jews lived on top of each other.

When they went to the toilets, dug out of the ground in the courtyard, the refugees risked their lives: they were bombed by Russian planes attacking Budapest.

“At night, we couldn’t go to the bathroom, but we risked losing our sleeping space, which would be taken by someone else before we returned. The previous owner would go into a rage. I tried to cover my ears so as not to hear. The wronged party would end up sleeping on a chair or on the floor. If one of us turned the other way, the neighbor had to turn too. But the Glass House was paradise, an oasis of security.”

Irena Braun,14 years old

As these were technically offices linked to the Swiss Legation, no civilians were allowed to make noise, as their presence was not authorized. They lived in hiding, in the basement.

A German air force unit even sent soldiers to supply the Glass House, thinking they were helping a Swiss diplomatic representation – and not realizing that it housed thousands of Jews!

The place fueled anti-Semitic hatred in Budapest. In early December 1944, the militia planned a roundup and execution in the Pálvölgy caves. A unit of the regular army was assigned to the task. The project was never carried out.

There was nevertheless a militia attack on December 31, 1944, led by Mihaly Balog. In the panic, three people were killed and seventeen wounded. It was narrowly thwarted. Frustrated by their failure, the militia returned the following day and executed the owner of the “Glass House” on the banks of the Danube.

The Protected Houses

Lutz was aided in his action by his wife Gertrud (declared Righteous in 1978) and by the Halutzim, a group of Jewish resistance fighters who provided the logistics for the rescue operation. Other diplomats from the Swiss Legation supported the rescue operation: Minister (Ambassador) Maximilien Jäger, Ernst Vonrufs, Peter Zürcher and Harald Feller (declared Righteous in 1999).

Soon, the protection papers were no longer enough. To strengthen consular protection for Jews, Carl Lutz imagined extending it from individuals to buildings. The idea was particularly ingenious.

This protective measure, which was an extension of his original prerogatives, called for all his “Jewish migrants” scattered across the city to be grouped together in a dedicated district – and thus avoid mistakes in the event of roundups. Neither Budapest nor Berlin wanted to arrest legitimate holders of letters of protection, and thus have to deal with complaints from the Swiss state.

Strategically, Lutz presented the measure as a “transitional measure before emigration” to overcome the SS’s reluctance. On paper, the logic was unstoppable. Hungary agreed. It made its gendarmerie available and defined the “protected” district.

3,969 Christian Hungarians were evicted, with the assurance that they would return to their homes at the end of the war. The rental costs of $10,000 (a considerable sum for the time) were borne by the Swiss Legation, which had no budget. In the end, two Jewish refugees paid the bill.

Lutz placed several dozen Palatine buildings on the same street (Pozsonyi út.) in the Újlipótváros district under diplomatic immunity. This enabled him to call the police if Hungarians or Germans entered the premises, as it was now protected territory. The tactic was copied by Sweden, then Spain, Portugal and the Vatican, all claiming to harbor Jews, presented as their nationals. In all, the diplomatic community in Budapest placed 32,000 Jewish refugees in an “International Ghetto”, two-thirds of them under Swiss flag.

Reporting to his Head of Department (Minister), Federal Councillor Pilet-Golaz (December 8, 1944), Carl Lutz explained that he was offering consular protection to the number of Jews for whom he was officially responsible: “7,800 people, in 25 houses.” In reality, according to Wallenberg’s report (December 12), the Swiss Legation was protecting 23,000 civilians, holed up in 76 buildings along the Danube. The Swiss diplomats had neither the staff nor the supplies to manage such an improvised refugee camp, in appalling conditions.

“I was completely alone in the face of growing legal problems. With no administrative apparatus, no financial means and no official mandate”.

Carl Lutz, 1946

Every day, Lutz and his wife risked their lives fighting against the illegal roundups carried out by the Hungarian fascist militia (Arrow Cross). While Carl was threatened with a pistol, Gertrud Lutz offered the militiamen Swiss chocolate to soften them up.

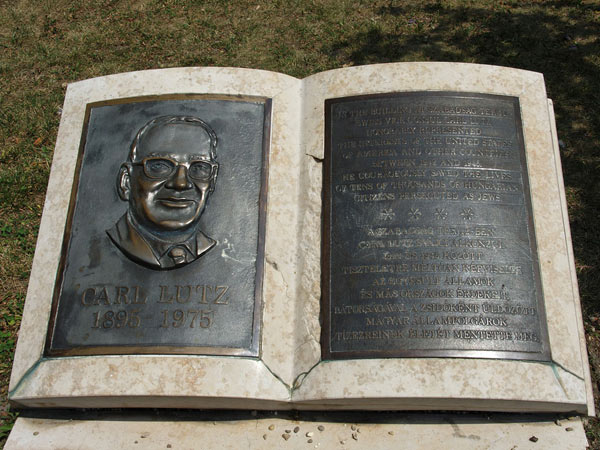

Today, a commemorative plaque is affixed to the bottom of every protected building, and the quay next to the Hungarian Parliament is named after Carl Lutz.

The "Death march"

On October 15, 1944, the Hungarian government collapsed, and the Arrow Cross militia took power. The SS took advantage of the situation to resume persecution. This time on foot, towards Austria.

In response, the Jewish resistance groups no longer respected Lutz’s strategy of limiting the number of forgeries in circulation in order to hide the fraud.

The 550 young Jews who made up the Jewish resistance, almost all teenagers (average age 18-20), were astonishingly audacious. The number of counterfeit Swiss papers exploded (nearly 30,000), and their quality plummeted. The resistance screwed on fake Swiss diplomatic plates, opened “false consulates” with counterfeit flags, forged stamps with Swiss heraldry and set up fake offices in the national colors. On Perczel Mór street, right next to Lutz’s official premises at Freedom Square, a fake Swiss office managed by Jewish youth was so credible – and silently approved by Lutz – that the Hungarian police… sent a cordon of mounted policemen to manage the crowd.

The whole thing was more or less done with the approval of Carl Lutz. Who was soon overwhelmed. “I knew that the [resistance networks] were producing false papers for various rescue operations, but the volume of this production far exceeded what I thought,” said the Swiss civil servant after the war.

The young Jews who copied the official seals, often in the darkness of a cellar, improvised: the text was shaky, the address incomplete, the heraldry lame. Sometimes, they confused the Swiss flag (white cross on red background) with the inverted Red Cross flag. In addition to protection documents, they produced housing certificates, Christian birth certificates and service books for the SS-Maria Theresia division – some Jews disguised themselves in Nazi uniforms to fight.

From November 8, 1944, 40,000 civilians were dragged 240 kilometers to the Austrian border. Lutz authorized his staff, using diplomatic vehicles, to drive up the columns to exfiltrate, as far as possible, Jewish refugees, declared on the spot to be “migrants”, “Salvadorians” or even “Swiss”, even though the unfortunates sometimes presented store bills as IDs.

“It was reported to me that when the marching Jewish columns were heading towards the Reich, emissaries from the Swiss Legation followed one column. They distributed protective passes to the marching Jews in such large numbers that by the end of the day, the majority of the column had disappeared, since the passes issued were respected by the accompanying Hungarian soldiers.”

Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Director of the Reich Central Security Office (RSHA), Berlin, November 11, 1944

The rescue effort was so extensive that the Reich Central Security Office (RSHA) sent a telegram of complaint to Budapest. In his correspondence, the German plenipotentiary in Hungary asked Berlin whether it should “dispose” of the Swiss official, in what amounted to an unanswered request for his elimination.

In response, the fascist Hungarian state forced Lutz to go to the starting point of the march (the Obúda brickworks) to differentiate between genuine and forged papers. The experience traumatized him: “I’ll never forget those frightened faces. The police had to intervene many times, as people almost tore off my clothes in their pleas. It was their last expression of life before resignation, which so often ended in death.”

According to correspondence between Lutz and Mantello, the vice-consul took advantage of his presence at the Obúda brickworks to hand out forged papers, letters of protection and also certificates of El Salvador nationality, to Jews waiting in the waiting area, terrorized and “beaten with dog leashes”. The majority of recipients survived.

From then on, official protection was no longer respected. When Swiss officials called the police to complain about raids, they were told “Swiss protection, or Jewish protection?” Several Lutz houses on Pozsonyi Street were rounded up, and refugees deported to the Bergen-Belsen camp or thrown into the river, tied together with barbed wire. In mid-December 1944, Carl Lutz dived halfway into the frozen Danube to save a Jewish woman. He saved her life.

"The Soviets surround us"

The Russians attacked Budapest, in what would become one of the most violent urban battles of the war. The siege of the city began.

Carl Lutz spent Christmas 1944 locked up with his staff in the Residence on Buda Hill, under artillery fire.

“I’ll never forget the dramatic days we lived through in January 1945, when twenty bombs fell on our house, which was completely destroyed by fire in two days. It’s a miracle that the 3,000-liter fuel tank in the courtyard didn’t explode, and that the cellar held out. We didn’t know if we’d end up in that cellar, buried under the burning ruins. Fortunately, the ceiling held.

Finally, in mid-February: liberation. Russian soldiers invaded and shouted “Chassi, chassi” (watches, watches) because they knew we were Swiss. They took our watches and threw themselves on the alcohol. They weren’t picky; they even drank the cologne bottles.

My mother was worried that I might be afraid of the soldiers’ brutality, so she told me to hide under the bed and keep quiet. So I did. A Russian shot under the bed. I didn’t move. My mother turned livid. When the soldiers left, I emerged from under the bed unharmed. I had a guardian angel.”

Agnes Hirschi-Grausz, Honorary President, Carl Lutz Society

The Swiss rescue efforts continued under the leadership of two employees, Ernst Vonrufs and Peter Zürcher, both of whom were declared Righteous Among the Nations.

On January 18, 1945, the Glass House was taken over by the Soviet 18th Guards Infantry Corps, in gloomy silence.

Budapest was liberated in ruins on February 13, 1945.

Lutz emerged from the rubble with his staff, unharmed despite the siege. The encounter with the Red Army was particularly dangerous. The Swiss civil servant escaped a rifle salvo and had to jump through a window. “They were looking for Hitler, but he was in Berlin,” he recalled, somewhat shocked.

“I, or rather we, had been confined [in the Glass House] for months, away from these horrors. Although we had received terrifying information here and there, the sudden shock of witnessing this destruction, on such a grand scale, with my own eyes, was simply overwhelming. […] The sight of Budapest that day dug a deep fissure in my soul.”

Irena Braun, 14 years old

Official silence and belated homage

At the end of the war, Carl Lutz, like other diplomats, was expelled by the Soviets. He returned to Switzerland, where he received an indifferent welcome.

In 1949, having divorced, Carl Lutz married Magda Grausz, the Jewish woman who had come to ask his protection for her and her daughter Agnès.

On a professional level, the return was difficult: two Swiss diplomats were imprisoned in Moscow, and Berne opened an administrative inquiry into the Legation in Hungary. Lutz was interviewed. Under oath, he explained that he had been authorized by Great Britain to manage a quota for “families”, repeating the subterfuge that had been at the heart of his rescue operation, when his Division had to manage 7,800 “individuals”.

Onsite, Lutz had – at least – protected three times as many. Nobody had the means to check. Countless refugees had lived underground, under the radar. In the eyes of the authorities, they didn’t exist.

Judge Kehrli failed to grasp the subtlety. Carl Lutz remained silent. The tens of thousands of abusive letters of protection, the distribution of thousands of forged Salvadoran papers, the illegal delivery of American, Swiss or other countries’ citizenship were not on the record. The investigation, which was mainly focused on another subject, was dismissed.

In the end, the Federal Administration only accused Lutz, in a letter, of “abusing his powers” by declaring the collective passports “Swiss” – fearing that Jews could seek asylum in Switzerland. On the other hand, the Federal Political Department was unaware that its employee had himself been involved in the creation and delivery of false papers to Jewish refugees. The State would find out later… Lutz was then protected by a certain notoriety abroad. Times had changed. Both Carl Lutz and Georges Mantello (himself threatened with expulsion) benefited from the change in society’s opinion of the victims of the Holocaust.

Within Swiss diplomacy, on the other hand, the silence surrounding the rescue operation was tantamount to disavowal. One Swiss Ambassador described Lutz as “a partisan member of the opposition, not an impartial and balanced third party”. Deeply affected, Carl Lutz refused a transfer to Baghdad, Iraq. He was transferred to the Defense of German Interests in Zurich, then to the Secretariat for Injured Property in Japan, in Berne. In 1960, he completed his career as Consul General in Bregenz (Austria). He retired in 1961 and died in Berne on February 12, 1975.

In 2020, Leiden University published a thesis tracing the difficulties surrounding Lutz’s memory in Switzerland. Some of the reasons were linked to the man himself and the way he raised the issue internally. Indeed, as Lutz was still in service, he revealed the extent of his involvement only belatedly, and did not publish his own recollections. However, the subject also remained taboo in Berne for political reasons. It raised sensitive questions about neutrality, the relationship between a State and its protecting power, and the Allies’ reaction to the Holocaust.

In 1961, on the occasion of the Eichmann trial, the Swiss government was concerned that light was suddenly being shed on its little consul. Bern was worried that Lutz might take the stand and reveal details of his experiences. In fact, Lutz had a frank look at the events : “[In Jerusalem] I could testify that when the troops of the German army and Himmler’s Einsatzkommandos marched in, the Western powers and the neutral states, with the exception of Sweden, remained passive in the face of the mass deportations”.

Far from these historical considerations, the other Swiss Righteous from Budapest, each in their own way, experienced an extraordinary destiny. Lutz’s ex-wife, Gertrud, named Righteous in 1978, had a brilliant career as a humanitarian in Poland, Turkey and Brazil, where she was nicknamed “the Angel”. She rose to become Vice-President of UNICEF, the UN children’s agency, in Paris. Her papers are now preserved in the archives of the Swiss feminist movement.

Harald Feller, a young diplomat, risked his life to save Jews, including a future Federal Court judge. Imprisoned by the Soviets in Moscow for a year, he left the diplomatic service on his return to Switzerland to serve his home canton of Berne as a magistrate. He was named Righteous Among the Nations in 1999.

Peter Zürcher and Ernst Vonrufs, two of Lutz’s civilian employees, were honored as Righteous in 1999, as was Friedrich Born, Swiss delegate for the Red Cross in Hungary (honored in 1987). Born’s work is regarded as one of the ICRC’s most decisive contributions to the civilian population during the war.

Carl Lutz was the first Swiss citizen to be recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by the Yad Vashem Memorial – in 1964. He was nominated three times for the Nobel Peace Prize, and has been honored in Germany (Order of Merit, 1962), Argentina, the USA and Israel. In 2014, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal by his alma mater, George Washington University. Thanked by the President of the Hungarian Council of Ministers in 1948, Lutz was honored at the end of the Cold War with a Quay and two monuments in his name, on Dohany Street and Liberty Square, in Budapest. In 2023, his daughter was awarded the Gold Cross of Hungarian Merit.

Honored by his home village in Appenzell, the civil servant was ignored in his own country, apart from a mention in a speech by Federal Councillor Feldmann – aside of a report on migration in 1958. The internal reasons were obviously political. Externally however, some social behavior might be also at stake, as Switzerland had little tradition of honoring individual initiatives, humanitarian or not.

Recognition came after 1995, in the wake of the Bergier Commission. The government was ready to take on a new, more objective and balanced vision of its history. Switzerland remains one of the few countries to have made such an introspective effort on WWII.

In 2018, Berne named one of the rooms in the Federal Palace after the Swiss Righteous of Budapest, and Parliament rose to greet the families in plenary session.

In 2021, Geneva paid tribute to them with an exhibition inaugurated by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, while the United States dedicated a room in its Embassy in Budapest.

Ongoing research

The scale of the rescue by Carl Lutz and the Swiss Righteous is often misrepresented, with excessive estimates taken from a letter written in 1948 by Mihaly Salamon (62,000 people protected).

These figures are an undocumented personal estimate. It is considered unreliable by several renowned historians, and excessive by the Hungarian Holocaust Memorial. The reality is probably lower than this estimate.

The Carl Lutz Society has carried out research on the subject, based on unused archives in its possession, and presented it at a symposium in Warsaw in 2021.

In 1962, the great historian Jenő Lévai, commissioned by Hungary after the war to study the Jewish tragedy, spoke with Carl Lutz himself on the subject. Lévai presented his analysis: he spoke of “26,000 Jews” under the direct protection of the Swiss Legation, without being disavowed by the vice-consul.

Other estimates put the rescue figure at 40-50,000, around the reasonable estimate of the number of letters of protection in circulation in Budapest. Indeed, some Jews benefited indirectly from the Swiss effort. Lutz validated, at least in part, the massive falsification effort carried out in parallel by Jewish resistance networks, which he covered in his correspondence with the Hungarian authorities. This lends credence to higher estimates.

The subject continues to be debated. It is impossible to give a definitive estimate for an illegal rescue operation.

Whether the estimate is high or low, the Swiss rescue, led by Carl Lutz, is now recognized as the largest diplomatic protection effort of the Second World War.

In the absence of precise figures, it’s fair to say that “several tens of thousands of people” were saved.

The survivors and their families now live in over twenty countries.

“These [Jews] were Hungarian citizens, which deprived them of diplomatic protection. But the laws of life are stronger than the laws of men.”

Carl Lutz, 1946